The Ecological Role of Parasites Explored in Predator-Prey Interactions (part 1)

Published:

Sometime last year I was reading Parasite Rex by Carl Zimmer when I came across the following passage:

Parasites may not only mark good ecological health; they may actually be vital for it. When ranchers overgraze their cattle and sheep on fragile grasslands, they can tip the ecology of the region over into a desert. As far as ecologists can tell, this move is pretty much irreversible, because the desert shrubs reorganize the soil in such a way that grasses can't penetrate back in... Ranchers usually dope up their livestock with medicine to kill as many intestinal worms as they can, but the parasites might be able to keep the livestock in a careful balance with the grass they depend on.

Parasites tend to carry a very a negative appeal, hence why many would be hesitant to admit that they can present a beneficial role in their respective ecosystems - but they can! As Zimmer speculates in the passage above, parasitism of ruminants could help prevent the desertification of pastures. Parasites accomplish this in a variety of ways, including by reducing host fecundity (in extreme cases, even castrating the host), reducing host lifespan, or making the host more vulnerable to predation. Clearly parasites have some population limiting potential and, depending on the circumstance, this could benefit the stability of the ecosystem or hinder it.

Parasites acting as "stabilizers" is a well-documented phenomenon, and Zimmer is not the first to speculate as to its existence. Six years prior to the publication of Parasite Rex, the French biologist and parasitologist Claude Combes published a paper in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation exploring the various roles that parasites play in their ecosystems [2]. Broadly speaking, these roles he characterizes as either stabilizing or destabilizing. Parasites behave as stabilizers when they regulate predator-prey relationships (e.g. by preventing over-predation) and prune population genotypes, thereby preserving the gene pool of the host species. The direct or indirect consequences of these effects stabilize the system by limiting the growth of one of the species, or in some instances preventing territorial encroachment by other species (see [2] for more discussion on this).

I will touch on a few examples in detail, as these were the first I found when I set about exploring this subject. Haemonchus contortus, or the barber's pole worm (so named because of how the ovaries appear on female worms), is a parasite of ruminants [3]. The blood sucking nematode has been responsible for major losses worldwide related to this industry, most heavily felt in populations of cattle, goats, and especially sheep. The larvae are ingested when the animal is grazing, and develop into adults within the abomasum of the host. The females mate and begin egg production only a few weeks after ingestion. The eggs are then released back into the pasture through the feces of the host, where the life cycle repeats. Symptoms of infection include anemia, weight loss, and even death, to name a few [3]. Although I am not aware of any study looking at H. contortus and its regulatory effects on wild ruminant populations, it is by no stretch of the imagination that this parasite is capable of suppressing ruminant populations, reducing the likelihood of overgrazing, following Zimmer's hypothetical scenario in the passage above.

In his paper, Combes touches upon other examples of the stabilizing behavior of parasites. Imagine a scenario in which two organism populations are geographically separated. Denote these populations by A and B. There is a parasite that infects both populations, but suppose that Population B is much more tolerant to infection than Population A and acts as a reservoir for the parasite. Population A, on the other hand, is not nearly as capable when faced with parasitic invasion, and infection more often than not means death. When climatic factors are favorable, Population A explodes in size and will spread into the territory occupied by Population B. Since Population B is a reservoir of the aforementioned parasite, however, the parasite infects members of Population A when the populations mix. The parasite spreads rapidly throughout the now burgeoning population. What follows is a massive kill-off of Population A, ending the population increase and leaving only enough members to repopulate Population A's orginal territory.

In this situation, the role of the parasite is stabilizing, as Population A is unable to encroach on or invade the territory occupied by Population B. One may even argue that this limits cross-breeding as well, as hybrid genotypes could be more vulnerable to parasitic invasion. A natural example of this is discussed briefly in [2], specifically in [4,5]. In these works, the hypothetical Populations A and B are the two rodent species M. vinogradovi and Meriones persicus, respectively, while the parasite is Y. pestis.

Parasites can also act to destabilize ecologies, and this is most often the result of human intervention (see some of the examples presented in [3]).

In the previous paragraphs, I've outlined some of the ways that parasites can act to stabilize their ecosystem, and mentioned some specific examples. This is all very interesting, but are we able to observe stabilizing behavior in a mathematical/computational model? In particular, can we model a system in which the parasites behaves as a "stabilizer," coexisting with other species and serving a regulatory role in its ecosystem? The answer to this is yes!

As a first step in these projects, it helps to choose a parasite/host relationship to help ground oneself. I was interested in exploring predator-prey-parasite relationships, and the hypothetical example suggested by Zimmer seemed like a good first step. In the case of this example, the "predator" is the grazing ruminant, the "prey" is the grass, and the parasite plays its own role in both scenarios. We are already familiar with a well-known ruminant parasite - H. contortus. Given its economic footprint, there is a plethora of information available on the life cycle and epidemiology of H. contortus infection, making data acquisition and parameter estimation a much easier process. As mentioned above, the worm develops into the infectious stage of its life cycle while in the pastures of grazing ruminants. When the ruminants ingest the infectious larvae as they are grazing, the blood-sucking parasites breed within their hosts. Female worms have a very high fecundity, producing anywhere from 5,000 - 10,000 eggs per day within only weeks after host invasion [6], but this varies considerably [7].

My first program exploring this predator-prey-parasite relationship was a sheep-parasite-grass model in NetLogo. The purpose of this computational experiment was to incorporate empirical features of both the host and the parasite, while still keeping things simple. The sheep in the simulation feed on discrete patches of grass. When a patch of grass is consumed by a sheep, it changes color to brown (indicating a lack of grass!) and the sheep gains a certain amount of energy. The grass will regrow over a specific period of time, or "ticks" in the case of NetLogo. Sheep will expend exactly half their total energy when lambing, and produce 1 to 3 lambs per lambing. The period of time between the egg and infectious larvae stages of the parasite are ignored, so that worms are assumed infectious as soon as they are excreted in the feces of hosts. A sheep becomes infected after feeding on a patch of grass that contains the infectious larvae. The larvae are only capable of surviving outside a host for a short period of time. Whatever amount of larvae is ingested by a sheep, only a certain proportion live to adulthood. The lifespan of the worms within the sheep depends on the initial dose of parasitic larvae, as found in [8]. The authors in [8] found that the higher the initial dose, the shorter the lifespan of adult worms, indicating some form of density-dependence in parasite mortality. Density-dependent effects were not observed regarding parasite fecundity [8,9]. The only density-dependence incorporated in the model is host death and fecundity. As the parasitic load of a sheep increases, the number of lambs produced during lambing is decreased, as is the life expectancy of the host sheep. Furthermore, the energy obtained via consumption of grass is also a decreasing function of parasite burden. An example of a trial run of the final simulation is shown in Figure 1.

At first, pasture availability is the dominant feature limiting the grazing sheep population. As time goes on and parasite abundance in the environment grows, on the other hand, it is the parasite that is more influential in controlling the sheep population. Occassionally, the sheep population will shrink sufficiently to allow for a slight respite of parasitic abundance in the pasture. In response, the sheep population will grow, only to have the helminth population grow as well. This happens many times in Figure 1, and is just one emergent feature of interest in the simulation. The other emergent feature I was surprised to see is that a very small portion of the sheep population is infected at any point in time. This is observed in many natural systems of parasites and their distributions within their hosts. Parasite distributions tend to be very skewed, so that only a handful of the population at any point in time is infected. Just why this is the case is still debated. For example, it could be a consequence of host behavior increasing environmental exposure, or some genetic factor causing predisposition to infection. Many times, mathematicians will assume that the parasite is distributed within hosts according to a negative binomial distribution [9,10]. I will talk about this a little more later on. For now, it is important to mention that H. contortus exemplifies this distribution within its hosts, as shown in [9]. That is, only a small proportion of the ruminant population was found to carry the vast majority of within-host worms.

Unfortunately, as one can see with enough patience, the sheep population in Figure 1 will eventually go extinct. Remember that the idea was to explore coexistence between the species! I also wanted to move beyond an agent-based model, to one that was more amenable to analysis. Keeping it general, I considered a predator-prey-parasite model. This sort of model has been considered in the literature before [10-17]. However, these models possess certain drawbacks that I wanted to address in my model.

First and foremost, I wanted to model the transmission of a macroparasite, rather than a microparasite. For those unfamiliar with the distinction, microparasites tend to have short generation times and, as their name implies, are small (think e.g. bacteria and viruses). Macroparasites, on the other hand, have longer generation times and are much larger comparatively (think e.g. flukes and tapeworms). Macroparasites are typically what one means when talking about parasites. For the sake of clarity, I'll drop the "macro-" prefix from this point forward in recognition of this colloquial habit. For more on the distinction between macro- and microparasites, check out this webpage

Modeling parasite transmission in a population is different than modeling the transmission of a virus or a bacteria. Some of the major differences that need to be accounted for in a mathematical model include (i) different stages in the life cycle of the helminth, (ii) density-dependent host mortality, (iii) density-dependent parasite mortality and fecundity, and the (iv) distribution of parasites in the host population. Although this list isn't exhaustive, it is sufficient for the purposes of developing a simple model to work with. I'll provide a brief explanation of each point above and direct the reader to [10] for more details. Regarding (i), as mentioned above, a parasite has a life cycle with developmental stages facilitating movement between host(s). In the case of H. contortus, the parasite is infectious in its larval state when it is present in the grass of the pastures. After it is ingested, it will mature into an adult, where it will begin to search for a mate. In the case of H. contortus, these helminths are dioecious (i.e. there is a male and female), so that egg secretion from a host can only occur if they contain sexually mature worms of each sex. For convenience, this consideration is ignored (see Table 16.1 in [10] for how this can be included in a parasite model).

Regarding (ii), the host's reaction to parasite invasion depends on the extent of their parasitic burden. A large parasite burden will necessarily result in more serious morbidity than a lesser parasite burden. This depends on the parasite being studied, but mortality as a result of infection is typically an increasing function of the number of within-host parasites. From the perspective of the parasite, (iii) mentions density-dependence as it effects parasite behavior. The more "cramped" a host is with parasites, the less eggs any single parasite may produce. Not only fecundity, but parasite mortality is also effected by the density of parasites within a host. Whether as a result of the strength of the immune response or competition for resources, helminth mortality tends to increase as a function of parasite density. This is the case with H. contortus, as shown in [8].

Points (ii) and (iii) claim that the progress of parasite invasion within a host depends on the amount of parasites within that host. On the scale of a population, then, helminth spread depends on the distribution of the parasites within the population, which is the final point (iv). The distribution of parasites within a population is nonrandom. This is due to a variety of reasons, the most common being repeated exposure to the source of the helminths (dependent on host behavior) and partial immunity as a result of repeated infections within the helminth. The extent that these factors contribute is still debated and depends on the particular helminth. In the vast majority of instances, the distribution is quite skewed. That is, a minority of the population ends up carrying the brunt of the number of within-host parasites. If we were to plot the density of the parasite distribution, it would look like a negative binomial distribution. Other distributions have been observed, but these tend to be only in controlled (lab) populations [10].

One final point not discussed but mentioned briefly in the previous paragraph is host immunity. Immunity against parasitic infection does not seem to operate in the same way that immunity to microparasites does. Continuing with the example of H. contortus, immunity is observed as greater resistance to parasitic challenge in previously infected sheep. The authors of [8] observed that infections of previously exposed lambs yielded lower numbers of juvenile worms than in the control group, indicating some partial immunity. This is confirmed by many other studies [18,19]. As with the case of H. contortus, immunity tends to be partial and not total. Given the complexity of this phenonemon, it is ignored in the subsequent model.

Incorporating these considerations into a mathematical model that is analytically tractable is a challenge, to say the least. The model will include the dynamics of three separate species: a predator and prey species, and a parasite. Since we want to keep things general, we will not focus on any particular species, contrary to how I began above with H. contortus. First it is important to determine how the parasite behaves. Does it parasitize the prey or the predator, or maybe both? How is the parasite ingested? Is it ingested from the environment, or during the consumption of the prey? Is the prey an intermediate host? Motivated by some of the research I've been doing lately, I decided to study a system in which the predator species is a host to the parasite. The host becomes infected with the parasite as a result of environmental exposure. The reason I chose this route was to study how the predator population would change with the introduction of a natural parasite, and if coexistence at a lower prevalence was possible.

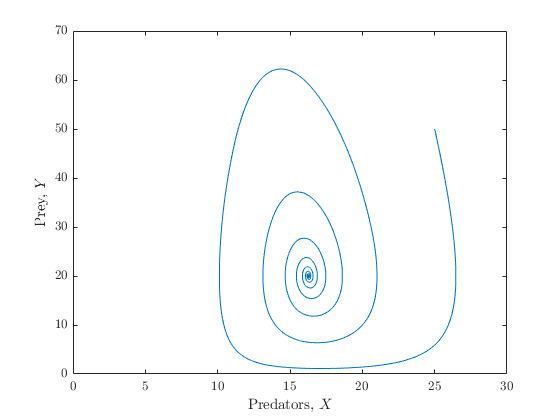

In the absence of the parasite species, the predator and prey dynamics should be normal. My interpretation of this is that if we set the parasite population to zero, the predator and prey dynamics are described by a Lotka-Volterra model Letting $X$ be the predator species and $Y$ the prey species, the model absent the parasite is

The prey population is regulated by a logistic growth rate $\rho$, with $K$ denoting the carrying capacity of the environment. The rate at which the prey species is consumed by the predators is given by $\delta$, and proportion $c$ of the consumed biomass is converted to new predators. Finally, the predator species dies at a natural mortality rate of $\mu_1$. A logistic growth rate was chosen instead of a constant growth rate in order to prevent the occurence of periodic oscillations in either population. A plot of the dynamics of the system in \eqref{LV} is given in Figure 2.

Now the fun part - adding in a parasite species. Since the predator acts as the host of the parasite, the equation governing the prey species will remain unchanged. As for the predator species, however, the predators will die at a disease-induced rate proportional to their parasitic burnen. Mathematically, we are only concerned with the within-host parasite population, as this population influences disease-induced host mortality, and within-host parasite mortality. Any other stage of the parasite's life cycle is ignored, and it is assumed that the parasites are taken up by the predators at a rate proportional to the number of infected predators. Before discussing the finer details of the assumptions made, I find it easier to first have a look at the actual system, which is as follows:

The predator-prey parameters (say that five times fast) are the same as when they appeared in \eqref{LV}, but we've now the added dynamic of a parasite population. This is incorporated by the extra compartment, as well as the inclusion of a parasite density-dependent mortality for the predators. This reflects the fact that host mortality is a function of their parasite burden. We can quantify this effect over the whole population by summing over the number of parasites a host possesses, denoted by $i$. In the above system, we sum over the number of parasites $i$, as well as the probability of possessing $i$ worms, $p(i)$. This is then multiplied by $\gamma$, which is the pathogenecity of the parasite. As for the added parasite compartment, parasite larvae, produced at a rate $\lambda P$, are assumed to be taken up at a rate proportional to the number of hosts. Only a certain proportion of these survive following ingestion, however, denoted by $d$.

Within-host parasites die at a density-independent rate, $\mu_P$, and at the rate that their hosts die. Once again, we sum over all $i$ to account for the distribution of parasites within the host population. The sum is simply the number of parasites per host. The number of parasites that perish with a host is $i$, and so we sum over all $i$ to account for the different probabilities. The rate of host death as a result of parasite burden is given by the term $\gamma X\sum_i ip(i)$, and so the number of parasites that die per density-dependent host death is $\gamma X\sum_i i^2 p(i)$. You'll notice that the former sum is the expected value of the distribution of parasites within the host population, while the latter is the second moment of the distribution. This will be important for the observation to follow.

Since we're dealing with probabilities, one is tempted to exclaim that our system is no longer deterministic. They would be right, but we can make an important simplification. As noted above, the sums represent the first and second moments of the distribution of parasites. If we choose a particular form for that probability distribution, these sums would have closed forms and our system would return to being deterministic. But, which distribution should we choose? It turns out that a majority of the time, parasite distributions within populations tend to follow a negative binomial distribution [10]. A negative binomial distribution may be described by its average, and a "clumping" or shape parameter, typically denoted $k$. Smaller $k$ values make the distribution more skewed, indicating a more aggregated distribution amongst the population - i.e., more "clumping." The mean number of within-host parasites is just $P/X$, and so we're armed with all the information we need to simplify the sums appearing in \eqref{fullModel}.

The first and second moments of a negative binomial distribution, with these parameters, are $$ E[X] = \sum_iip(i) = \frac{P}{X} \quad \text{and} \quad E[X^2] = \sum_i i^2p(i) = \left(\frac{k+1}{k}\right)\left(\frac{P^2}{X^2}\right)+ \frac{P}{X},\nonumber $$ respectively. Substituting these for the sums in \eqref{fullModel} gets

Although the system in \eqref{fullerModel} seems a tad complicated for our analytical tools to be of much use, there is still some interesting insights to be gleaned. The first step is of course equilibria quantification. The system in \eqref{fullerModel} possesses two meaningful equilibria, corresponding to parasite-free and parasite-present states. The parasite- free state, involving only competition between the predator and the prey, is

Rather obviously, the prey population at equilibrium, in the absence of any parasitism, is influenced by the per-capita rate of predation ($1/c\delta$), and the death rate of the predator. This equilibrium is stable when two conditions are satisfied. First, if the maximum growth rate of the predator population per unit time exceeds the death rate of the predators. That is,

The (much more complicated) parasite-present coexistence equilibrium is as follows:

Stability analysis of this equilibrium is not possible, given the complicated form of the populations. Nonetheless, we are able to state when the coexistence equilibrium is possible, which basically means finding when these populations are positive (and thus biologically relevant). From this, we may be able to make some statements about the relationship between the three species in the system. Looking at the predator population, this quantity is only positive if $k(\gamma + cK\delta + \mu_3) + cK\delta > \mu_1.$ This inequality is similar to \eqref{test2}, except now we've the added dynamic of the parasite. Recall that this parameter accounts for the distribution of parasites in the predator population. For $k \rightarrow 0$, we obtain \eqref{test2}.

The prey population in the coexistence equilibrium is positive only if the following expression is less than unity

Finally, the parasite population in the system is positive if all above inequalities are true, as well as if the inequality in \eqref{test} is reversed. In lieu of more thorough mathematical analysis, it has been established that the parasite-present equilibrium is positive only if the aforementioned inequalities are valid, which simultaneously means that the parasite-free equilibrium is unstable (agreeing with our intuition). A more thorough approach could involve establishing that the populations in the system are bounded (the parasite population is limited by the number of predators is limited by the number of prey), verifying that the populations do not go extinct, proving the nonexistence of certain dynamical behavior (periodic solutions and all that), and then establishing more rigorously the conditions required for a solution to converge to the parasite-present equilibrium.

However, I just realized that this blog post is quite large (a nearly 30 minute read, according to the counter), so I will put off any numerical results/discussion for a later post! Hopefully this post has intrigued you and made you think about the indispensable ecological role that parasites can play!

References

[1] Zimmer, C. Parasite Rex. The Free Press, 2000.

[2] Combes, C. Parasites, Biodiversity and ecosystem stability. Biodiversity & Conservation. 1996; 5.

[3] Emery, D.L., Hunt, P.W., Le Jambre, L.F. Haemonchus contortus: the then and now, and where to from here? International Journal for Parasitology. 2016; 46(12).

[4] Golvan, Y.J. and Rioux, J.A. [The ecology of Meriones of the Iranian Kurdistan. Its relation to the epidemiology of rural plague. (Survey of the Institut Pasteur de l’Iran. Preliminary report)]. Annales de parasitologie humaine et comparee. 1961; 36.

[5] Golvan, Y.J. and Rioux, J.A. La peste, facteur de régulation des populations de mérions au Kurdistan iranien. La Terre et la V/e. 1963; 1.

[6] Sinnathamby, G. et al. The bacterial community associated with the sheep gastrointestinal nematode parasite Haemonchus contortus. PLoS One. 2018; 13(2).

[7] Coyne, M.J. and Smith, G. The mortality and fecundity of Haemonchus contortus in parasite-naive and parasite-exposed sheep following single experimental infections. International Journal for Parasitology. 1992; 22(3).

[8] Coyne, M.J., Smith, G., and Johnstone, C. A study of the mortality and fecundity of Haemonchus contortus in sheep following experimental infections. International Journal for Parasitology. 1991; 21(7).

[9] Barger, I.A. The statistical distribution of trichostrongylid nematodes in grazing lambs. International Journal for Parasitology. 1985; 15(6).

[10] Anderson, R.M. and R.M. May. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. Oxford University Press, 1991.

[11] Freedman, H.I. A model of predator-prey dynamics as modified by the action of a parasite. Mathematical Biosciences. 1990; 99(2).

[12] Das, K.P. A Mathematical Study of a Predator-Prey Dynamics with Disease in Predator. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2011; 2011.

[13] Hadeler, K.P. and H.I. Freedman. Predator-prey populations with parasitic infection. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 1989; 27(6).

[14] Anderson, R.M. and R.M. May. The invasion, persistence and spread of infectious diseases within animal and plant communities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London.

Series B, Biological Sciences. 1986; 314(1167).

[15] Packer, C., et al. Keeping the herds healthy and alert: implications of predator control for infectious disease. Ecology Letters. 2003; 6.

[16] Anderson, R.M. and R.M. May. Regulation and Stability of Host-Parasite Population Interactions: I. Regulatory Processes. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1978; 47(1).

[17] May, R.M. and R.M. Anderson. Regulation and Stability of Host-Parasite Population interactions: II. Destabilizing Processes. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1978; 47(1).

[18] Schallig, H.D. Immunological responses of sheep to Haemonchus contortus. Parasitology. 2000; 120.

[19] Santos, M.C. et al. Immune response to Haemonchus contortus and Haemonchus placei in sheep and its role on parasite specificity. Veterinary Parasitology. 2014; 203(1-2).