Sterile screwworms

Published:

Cochliomyia hominivorax (Coquerel) (Diptera: Calliphoridae), otherwise known as the New World Screwworm (NWS), is a pest of livestock. The females of this species oviposit their eggs within the open wound of a warm-blooded host. After the eggs hatch, the larvae feed on the living tissue, which can result in severe complications and even death of the host. NWS has been eradicated in the United States and many Central American countries, but is endemic in South America and several countries within the Caribbean Region, including Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Jamaica.

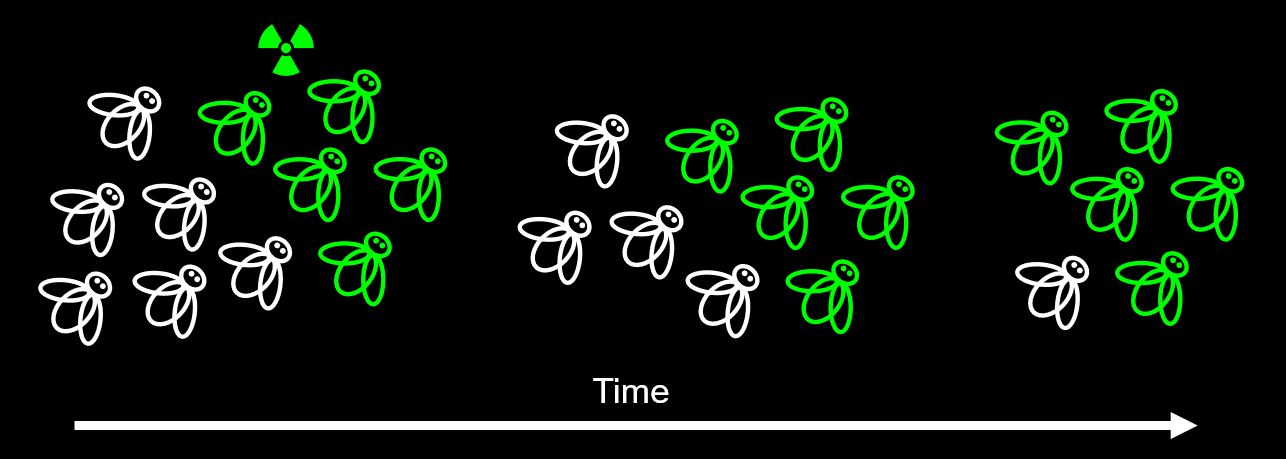

The widespread eradication of NWS was the first (and most successful) application of the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), which involves the release of sterile males to crash a pest population. By releasing sterile males in large numbers, females are more likely to mate with a sterile male than one that is fertile. This leads to a population decline and eventual collapse. SIT is rather inefficient compared to other forms of genetic pest control, as successful control relies on regular mass releases of sterile males. This idea is illustrated in Fig. 1. NWS lends itself quite nicely to control by SIT, as it has a relatively short generation time, and the females tend to only mate once in their life [2, 3], just like mosquitoes.

We simulate SIT within an idealized NWS population to see what conditions are required to achieve eradication. In addition to SIT, we also consider the use of gravitraps. Using chemicals that mimic the allure of an open wound (yuck!), gravitraps lure and kill gravid females, further contributing to population suppression.

We will keep the model simple and assume a population of $N$ fly pairs, or $N$ males and $N$ females (so there are $2N$ flies total). We ignore age structure and study the population per generation. Releases occur weekly and are quantified by the ratio of released sterilized males to normal--or wild-type---males. Let $\rho$ denote this ratio. For example, $\rho = 2$ means that two sterilized males are released for every wild-type male. Since our model updates every generation and not every week, the proportion of female matings that is with sterile males is $\rho^*/(\rho^* + 1)$ for $\rho^* = \frac{G}{7} \rho$ and $G$ the generation time of NWS in days. Each adult female produces $\lambda$ female progeny that will survive to oviposit. Finally, let $\eta$ denote the trapping effectiveness, or the proportion of females that are caught and killed by traps before ovipositing. The adult female population at generation $i$, $F_i$, is given by the following statistical model.

\(\begin{aligned} F_i & \sim \text{max}\left\{\text{Pois}(\lambda Y_i), \ N\right\}, \\ Y_i & \sim \text{Binom}\left(X_i, \ 1- \frac{\rho^*}{\rho^* + 1}\right), \\ X_i & \sim \text{Binom}\left(F_{i-1}, \ 1-\eta\right). \\ \end{aligned}\)

The generation time of NWS is approximately 19 days, calculated using the life stage durations and survival probabilities provided in [4]. We assume a 4-day delay between female eclosion and oviposition [5], and take the average number of progeny produced throughout the lifetime of a female to be 200 [6]. Using this figure and the data from [4] produces a growth rate of $\lambda = 20$. In other words, each adult female produces 20 female progeny that will live to oviposition. This is exactly the value used in the models of [1].

Below is a Shiny app that simulates SIT control of NWS according to the model above. Hitting the "Plot" button shows the mean-field result, a 95% confidence interval, and other information depending on the simulation settings.

References

[1] Atzeni, M. G. et al. (1994). Comparison of the predicted impact of a screwworm fly outbreak in Australia using a growth index model and a life-cycle model. Med. and Vet. Entomol. 8(3); 281-91.

[2] Bushland, R. C., and D. E. Hopkins (1951). Experiments with screwworm flies sterilized by X-rays. J. Econ. Entomol. 44(5); 725-31.

[3] Crystal, M. M. (1967). Reproductive behavior of laboratory-reared screwworm flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Med. Entomol. 4(4);443-50.

[4] Matlock, Jr., R. B., and S. R. Skoda (2009). Mark–recapture estimates of recruitment, survivorship and population growth rate for the screwworm fly, Cochliomyia hominivorax. Med. and Vet. Entomol. 23(1);111-25.

[5] Thomas, D. B. (1993). Behavioral aspects of screwworm ecology. J. of the Kansas Entomol. Soc. 66(1);13-30.

[6] Thomas, D. B. and R. L. Mangan (1989). Oviposition and wound-visiting behaviour of the screwworm fly, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Ann. of the Entomol. Soc. of America . 82(4); 526–34.