Turnips and malaria

Published:

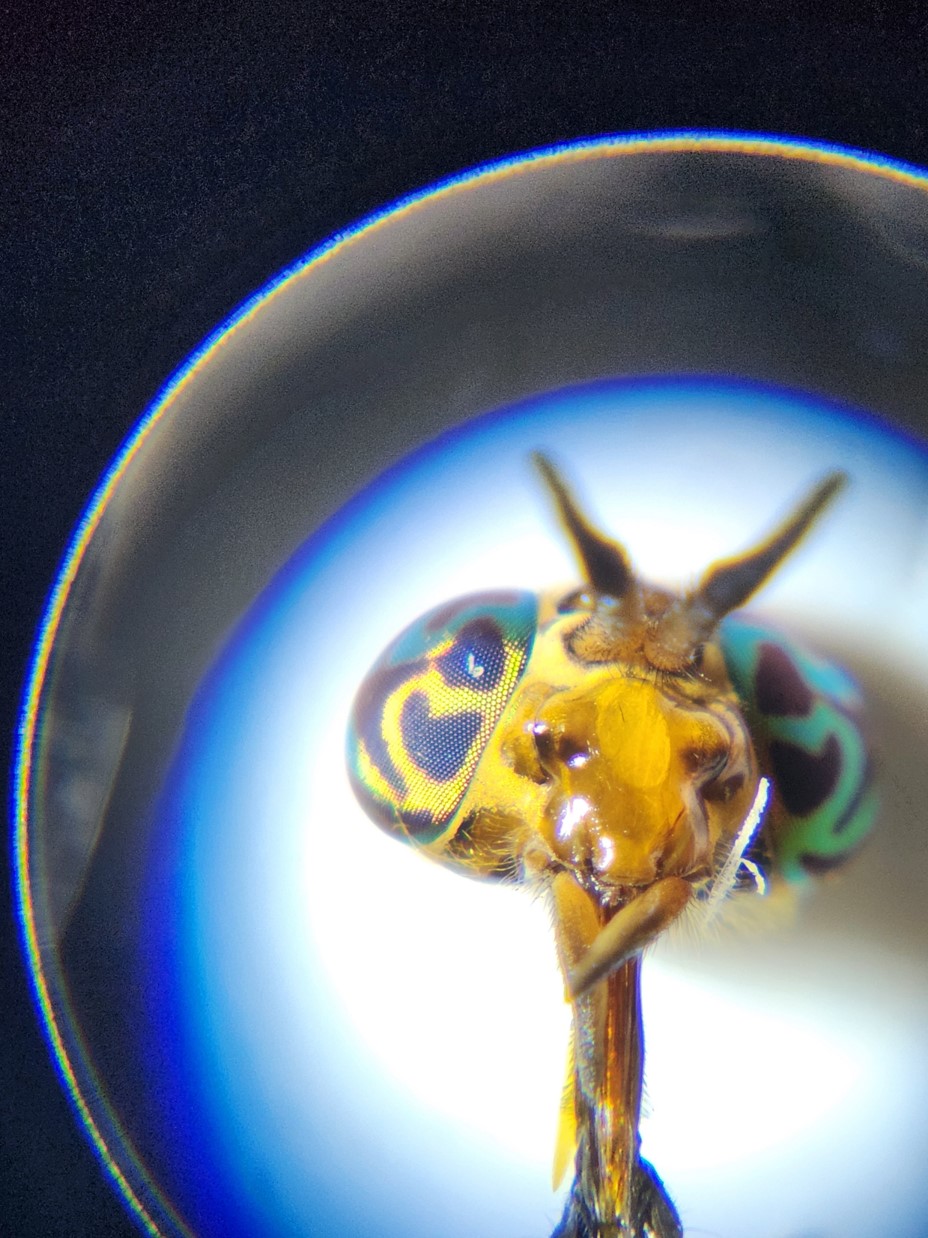

See below for a story draft I pitched some time ago on the disappearance of malaria from England. I was motivated to write this story after a discussion I had with Dr. Paul Reiter, who authored a paper on the subject. At the end, I've included some bug pictures I took this summer (2024) in Maine. These are the head of a deer fly and a female Aedes triseriatus!

It is a common misconception that malaria is strictly a disease of the tropics. This could not be farther from the truth---the reaches of endemic malaria in the 19th century stretched as far north as the Arctic Circle!

However, nowhere in the historical expanse of its occupation is the story of malaria’s disappearance more fascinating than in England, where the main protagonist is played by a vegetable: the turnip.

The name "malaria" is Italian in origin and literally means "bad air." This is because, prior to the popularization of germ theory in the latter half of the nineteenth century, people believed that diseases spread environmentally by a "miasma," or a form of polluted air. Malaria fit this description well: mosquitoes preferred the brackish waters of the marshes in the southeastern regions of England, where the air was often rank with the smell of decay.

We now know that malaria is caused by a parasite, called Plasmodium, that hitches a ride in the bite of infected mosquitoes. There are five species of Plasmodium that cause disease in humans.

Some mosquitoes will predominantly feed on humans, such as the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is responsible for transmitting yellow fever. Mosquitoes that prefer humans for their bloodmeals are said to be anthropophilic.

Not all mosquitoes prefer to bite humans, however; they also bite dogs, frogs, birds, and livestock. Mosquitoes that prefer biting other animals to humans are referred to as zoophilic.

It turns out that the mosquito species most likely responsible for spreading English malaria, Anopheles atroparvus, is zoophilic and prefers to snack on domestic farm animals, especially cattle. During the winter the females will seek shelter in homes and animal sheds, periodically interrupting their semi-hibernation to feed.

Farmers during the seventeenth century kept their herds small during the winter, so that when the female mosquitoes emerged to feed, humans were the most available target.

Enter the turnip. Up until this point in England’s history, farmers followed the fallow system: a farming technique in which a plot of land is left unsown, or fallow, between vegetative cycles to allow the soil to reabsorb lost nutrients.

Farmers discovered that plants such as turnips could be used to increase arable land efficiency. Turnips enjoy cooler weather, bring nutrients up from deep in the soil, and, most important to our story, serve as livestock fodder. Turnips could be planted in plots of land previously left fallow and simultaneously provide food for livestock during the winter. Now that farmers could feed their herds year-round, herd sizes would grow tremendously as a result.

With the increasing number of year-round livestock (especially cattle), humans became a less attractive target for the zoophilic mosquito An. atroparvus. Fortunately for us, the Plasmodium parasites that infect humans do not infect livestock.

So, the spreading popularity of the turnip to feed livestock in the winter increased cattle populations, which diverted the attention of the cattle-hungry mosquitoes. The parasitic passengers of these biting mosquitoes cannot infect livestock, so they would ultimately perish in the bloodstreams of their non-hosts.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, there were only 100 deaths due to malaria in England and Wales combined. The last handful of locally acquired malaria cases occurred in 1921. Since then, the only appearance of malaria in England has been imported.

Beyond changing farming practices, there were many contributing factors to the eventual disappearance of malaria in England. Other reasons that have been credited include improved drainage, construction practices, and nutrition. Nonetheless, the turnip played a crucial part, and is a lesson in the fascinating and incredibly complex ways in which our decisions influence the pathogens that infect us.