Gene drives and population suppression

Published:

Despite having this website for years, not one of my blog posts have been related to my thesis work. (I have written about some of my gene drive research, but that article is over on the SIAM News website). Most of my Ph.D. has been spent studying gene drives, or genetic elements that bias their own inheritance in target populations [1]. By target populations, I mean any pest species specific to some region. But then what is a pest species? Worner and Gevrey [3] define a pest species as

an organism that damages crops, destroys products, transmits or causes disease, is annoying or in other ways conflicts with human needs or interests

The list of organisms that fit this definition is quite long, as you could probably guess! The pest I work on most frequently is the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. A significant source of mortality and morbidity in humans, Ae. aegypti spreads a lot more than the virus responsible for yellow fever, but also those responsible for Zika, chikungunya, and dengue. Another pest species is the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus. This mosquito is important in the area of conservation, especially in Hawaii, where it has wreaked havoc on the local avifauna thanks to its role in transmitting the avian malarial parasite, as well as other harmful pathogens [2].

Broadly speaking, gene drives can be (roughly) divided into two categorites: population replacement and population suppression. Population replacement essentially involves genetically modifying an entire target population. For example, a desirable modification in mosquitoes is immunizing them against viruses harmful to humans. Population suppression drives, on the other hand, are designed to suppress or eradicate target populations. This is similar to existing control strategies that primarily rely on insecticide spraying. The difference is that gene drives are particular and regionally contained to a single (target) species. In practice, a population suppression gene drive is easier to develop because deleterious genetic modifications are easier to produce than genetic modifications that are both desirable to human interests and fit enough to replace a wild population. However, as we will see later in this post, these classifications are not disjoint.

What I wanted to explore in this post is the interesting behavior of population suppression drives. Population suppression is typically the first thing people think about when it comes to addressing the problem of pest species. How do you curb the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases? Kill the mosquitoes, of course! Many pest species of medical concern are also invasive, so their eradication/suppression will help restore native ecologies and be of little negative consequence to other species. In some scenarios, suppression can be the most practical option, such as with our earlier example of Cx. quinquefasciatus. How could you genetically modify these mosquitoes in a way that protects the avifauna of Hawaii and other threatened islands? You could immunize them against the avian malaria parasite, but then there is still the issue of West Nile virus and various avian poxviruses, all vectored by the mosquito [2]. On top of all this, Cx. quinquefasciatus is invasive, having been accidentally introduced to the island in the 1800s. Given the circumstances, eradication seems the most effective strategy. (I should mention that the question of population eradication is anything but simple and concerns important social and political matters beyond the perspective provided here [4]; this example is meant to be more illustrative of scenarios amenable to suppression/eradication, and not to minimize the complex process involved in such decision making.) Population suppression is not a straightforward matter, however. Pest species have consistently demonstrated their adaptability in the face of and resistentence against modern control strategies—partly the reason why gene drives have received so much attention in the first place.

Population suppression gene drives exhibit many interesting biological and mathematical phenomena (some of which I've pursured in my own research). But you don't have to take my word for it—that is what models are for! The following simple model was an afternoon idea to explore some of the rich dynamics in population suppression. The agent-based model below simulates a population of wild-type and transgenic (gene drive-bearing) organisms on a grid of cells. Each cell contains only a single individual at a time. Density-dependence is included, à la Conway, with the following rules:

- If the (Moore) neighborhood of a cell contains more than three organisms, the cell dies;

- If the (Moore) neighborhood of an unoccupied cell contains only two organisms, a new organism is produced in that cell.

Time is discrete and, during each time step (henceforth referred to as "tick"), organism mortality occurs with a certain probability. The mortality probability of wild-type and gene drive-bearing organisms is denoted as $\mu_{wt}$ and $\mu_{gd}$, respectively. For now, we take $\mu_{wt} = \mu_{gd} = 0.5$, so that the average lifespan for each organism is 2 ticks. When an organism is born (i.e., a cell becomes occupied), the genotype of the newly occupied cell is determined from the two "parents" (the two neighboring occupied cells). Two wild-type parents produce a wild-type offspring, while a gene drive-bearing parent only produces gene drive-bearing offspring—owing to that "biased inheritance" business mentioned at the very beginning. A simulation ends if it reaches 2500 ticks, or if either the total or gene drive-bearing population goes extinct. Drive-bearing organisms incur fitness costs that affect their lifespan and fecundity. Lifespan fitness costs affect per-tick mortality probability, while fecundity fitness costs affect the probability of an offspring being successfully produced following mating. For example, a $50\%$ relative fecundity means that there is only a $50\%$ probability an offspring is conceived from a mating involving a gene drive-bearing organism.

For now, we will assume there are no viability costs and keep the lifespans of each genotype the same. However, how does the fecundity of drive-bearing organisms affect performance? Let's take a look.

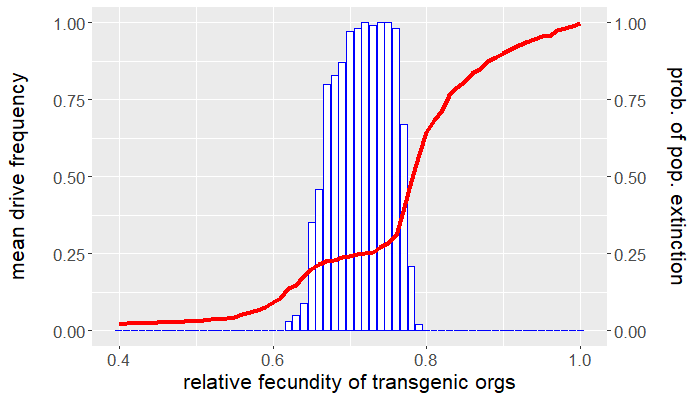

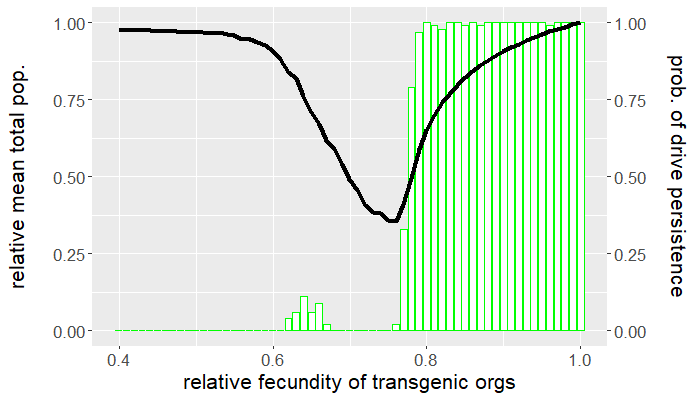

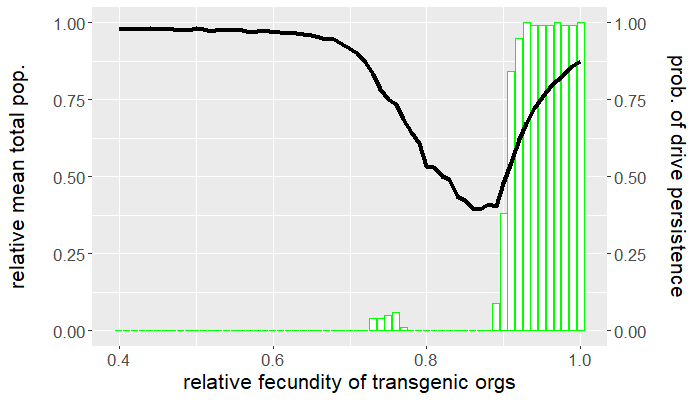

The program is coded entirely in NetLogo and the analysis is carried out in R. The population is seeded with a handful of wild-type individuals that are allowed to reach equilibrium for 50 ticks before a release of transgenic organisms occurs. The release ratio used, relative to the wild-type population at equilibrium, is $5\%$. We vary the relative fecundity of transgenic organisms between $[0.4, 1.0]$ and run 100 replicates for each set of conditions. For each simulation, we measure the number of gene drive and wild-type organisms following release. Figures 1 and 2 show the results of the first batch of simulations. The graph in Figure 1 gives both the mean gene drive frequency and probability of population extinction following release as the relative fecundity of transgenic organisms is varied. Figure 2, on the other hand, shows the mean total population relative to wild-type equilibrium as well as the probability of drive persistence, both as the relative fecundity is varied.

Here, "persistence" refers to the case in which gene drive-bearing organisms are not extinct by the 2500 tick simulation time cap. This suggests one of two possibilities: the gene drive-bearing and wild-type organisms "coexist" in cyclic fluctuations—dubbed "chasing" by some [5], or the gene drive has reached fixation and is unable to push the population to extinction. To elaborate on the former scenario, "chasing" occurs when the gene drive eradicates the population locally but is unable to achieve global eradication before residual wild-type organisms recolonize vacant patches of the landscape. If given the opportunity, the gene drive would eliminate the target population but, due to an imbalance between organism dispersal and drive load, what results is a cat-and-mouse game of transgenic chasing wild-type organisms across the landscape. An individual simulation illustrating this behavior is shown in Figure 3.

For what values of relative transgenic fecundity does chasing occur? One need only compare the bar charts in Figures 1 and 2 to find out. In Figure 1, extinction occurred in a majority of the simulations for a transgenic relative fecundity in the range $[0.67,0.77]$. For relative fecundity values in this range and below, we expect either the gene drive or the population to go extinct. In the range $[0.62, 0.66]$, there is a small "bump" in the persistence probability shown in Figure 2. Fecundity fitness costs in this range rarely produced extinction, but do not completely fall out of the population. We can thus confidently point to this region as where we expect chasing to occur in simulations—the lower persistence probabilities merely suggest that it is rare to have coexistence of the two genotypes at 2500 ticks. The probability of population extinction within this range suggests that the wild-type population most often emerges victorious in the pursuit.

Indeed, the results above show that only a narrow region of fecundity fitness costs (approximately $[0.67,0.77]$) is capable of reliable population elimination. If the fitness costs are too high, the gene drive fizzles out and goes extinct, or "chases" the wild-type in a game that favors a wild-type victor. If the fitness costs are too low, the gene drive fixes and persists in a suppressed (but not eliminated) population. In this case, the gene drive both technically suppresses and replaces the target population. Figure 2 shows that with fitness costs of approximately $20\%$ (corresponding to a relative transgenic fecundity of $80\%$), the population can be reduced by more than half. Depending on the target species, this could be more desirable than elimination, especially if we consider the possibility of organism immigration. However, this also raises a separate issue of gene drive resistance, which is beyond the scope of this post.

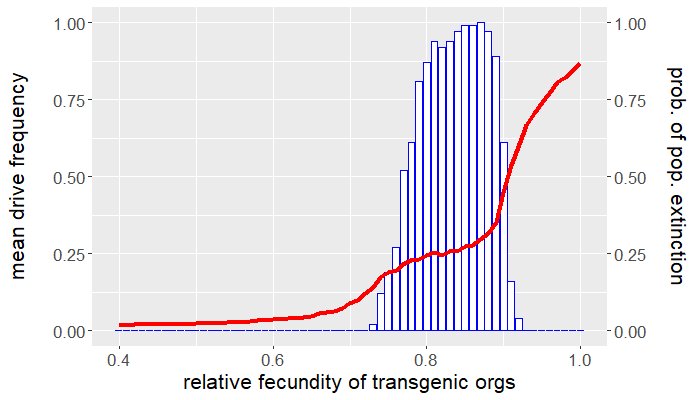

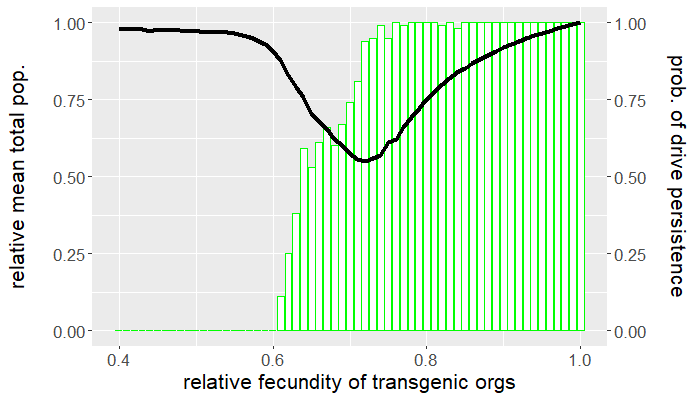

Up to this point, we have yet to consider any other fitness cost besides that affecting an organism's fecundity. How sensitive are the results above if we assume an additional viability fitness cost is incurred by gene drive-bearing organisms? Recall that we set $\mu_{wt} = \mu_{gd} = 0.5$, so that the average lifespan of either genotype is two ticks. Let's now take $\mu_{gd} = 0.55$, corresponding to an average lifespan of 1.8 ticks, and leave the wild-type mortality probability the same. How do things change? Repeating the experiments above but for this new parameter value produces the plots in Figures 4 and 5. Despite only a $10\%$ reduction in average lifespan, the viability fitness cost dramatically reduces the mean drive frequency, except for high relative transgenic fecundity.

Comparing Figures 1 and 4, not only is the mean drive frequency noticeably reduced, but the range of fecundity values resulting in population elimination a majority of the time is now $[0.77,0.9]$. This means that if the desired outcome is population eradication, there is little tolerance for reduced transgenic fecundity assuming (small) viability fitness costs. Similarly, the window for drive persistence is much smaller.

Clearly, there is a tradeoff between gene drive performance and how deleterious a gene drive can be. Increasing fitness costs improves performance to a point, after which performance dips precipitously. This also depends how and when the fitness cost occurs. It can be more effective for a fitness cost to act at a certain time in the organism's life cycle. Some organisms experience density-dependent mortality as larvae because of intraspecific competition. Imposing a viability fitness cost before this critical stage alleviates this source of natural mortality by reducing the amount of conspecific competition. It is instead preferable to impose viability fitness costs after the larval stage. The larvae of other pest species might be the most economically injurious stage of the organism's life cycle, in which case it would be best to impose a viability fitness cost prior to eclosion (e.g., a fitness cost that affects hatching rates). All this is to say that gene drive parameters depend on the objective of control. Persistent population suppression is better achieved by a gene drive that only reduces transgenic fecundity, while population eradication is possible for a gene drive incurring both reduced viability and fecundity, but only for narrow ranges in parameter space.

I briefly mentioned this above, but in what situations would persistent population suppression be useful? That is, why bother permanently reducing a population instead of eradicating it? Aside from the important social and political responses to this question, there is a simple ecological consideration: immigration. Organisms disperse all the time and, given the right conditions, can travel significant distances. In spite of our best efforts, it is possible that pest species can re-invade a region in which it was previously eradicated. This possibility becomes more dire if we factor in human-assisted dispersal. Indeed, the invasiveness of many pest species is overstated when accounting for the contribution of humans. The Asian tiger mosquito (Ae. albopictus) arrived in the United States aboard tires in the 1980s, the fruit fly Drosophila suzukii arrived in 2008 likely from fruits imported from Asia [7], ponds have been intentionally stocked with Mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) around the world since the 1920s, and trailering motorboats continues to propagate the invasive Eurasian milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), especially up here in Maine. Organism immigration is the rule rather than the exception. The (re-)invasion of crop and livestock pests might be managed well with reactionary control programs [8], but the situation is more complicated in the case of pests that vector diseases harmful to humans. Not only is there a vacant niche (unless it has been occupied by competitors), but there is also the problem of disease susceptibility depending on how long the pest has been regionally eradicated. In regions of the world where rapid responses to invasion cannot be mounted, it might then be more practical to opt for a gene drive that persistently suppresses the target population. In this case, the population is not eradicated, and new immigrants are "absorbed" into the suppressed population.

Let $\mu_{wt} = \mu_{gd} = 0.5$ as in the first experiment, but during each tick we introduce five wild-type organisms (approximately 1% of the population at wild-type equilbrium). Obviously, population eradication is impossible because new individuals are always being introduced into the population. How successful is population suppression in the presence of immigration? Figure 6 shows that, at best, the target population can be halved with extinction of the gene drive occurring in only $6\%$ of the simulations. Whether this level of suppression is acceptable depends on the target species. For mosquitoes, this is less than satisfactory. Then again, the size of the suppressed population depends on the frequency and size of immigration events. Note also that it is possible that the the population is both suppressed and replaced. This happens because the gene drive must already exist at a high frequency in the target population in order to absorb newly introduced immigrant organisms. If the gene drive carried a cargo affecting desirable change in the species, this level of suppression might be perfectly satisfactory (e.g., less nuisance biting and mosquito-borne disease immunity). An example of this outcome is shown in Figure 7.

My main goal with this afternoon project was to demonstrate some of the rich behavior exhibited by population suppression experiments in silico, introduce some of the considerations that go into gene drive design and use, and highlight several factors to consider when assessing gene drive performance, including proximal (non-random) mating and wild-type immigration. I grapple with these themes a lot in my professional work, but it is always nice to step back from the rigor of graduate school to remind oneself of why they enjoy research in the first place. Hopefully you, the reader, found this interesting as well.

References

[1] Alphey, L. S., Crisanti, A., Randazzo, F., and O. S. Akbari (2020). Standardizing the definition of gene drive. PNAS. 117(49); 30864-7.

[2] Harvey-Samuel, T., Ant, T., Sutton, J. et al. (2021). Culex quinquefasciatus: status as a threat to island avifauna and options for genetic control. CABI Agric Biosci. 2; 9.

[3] Worner, S. P. and M. Gevrey (2006). Modelling global insect pest species assemblages to determine risk of invasion. Journal of Applied Ecology. 43; 858-867.

[4] Myers, J. H., Savoie, A., and E. van Randen (1998). Eradication and pest management. Annual Review of Entomology. 43(1); 471-491.

[5] Champer, J., Kim, I. K., Champer, S. E., Clark, A. G. and Messer, P. W. (2021). Suppression gene drive in continuous space can result in unstable persistence of both drive and wild-type alleles. Mol Ecol. 30; 1086-101.

[6] Reiter, P. and R. F. Darsie, Jr. (1984). Aedes albopictus in Memphis, Tennessee (USA): an achievement of modern transportation? Mosquito news (USA). 44(3); 396-9.

[7] Rota-Stabelli, O., Blaxter, M., and G. Anfora (2013). Drosophila suzukii. Current Biology. 23(1):R8-R9.

[8] Lindquist, D. A., Abusowa, M., and M. J. Hall (1992). The New World screwworm fly in Libya: a review of its introduction and eradication. Med Vet Entomol. 6(1); 2-8.