Sexy Peacocks: The Mathematics of Sexual Selection in Birds

Published:

Saturday thunderstorms are a good excuse to update this website! I wrote this toy model one Saturday afternoon long ago, so I will take this Saturday afternoon to tell you about it. This particular project I presented at the most recent Triangle Area Graduate Mathematics Conference (TAGMaC) at Duke. The title of my talk was the same as this blog post.

Many of us are likely familiar with the ornamental garbs donned by peacocks (males of the species Pavo cristatus), but few might know of the comparatively duller plumage characteristic of peahens. If you live anywhere in the central or eastern United States, you do not have to look far to spot a cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis). During the summers in Maine, the males stick out in the green foliage with their red plumage and bright, scarlet beaks. The females instead dress themselves in a duller, earthy plumage. These examples illustrate a form of sexual dimorphism (a difference in size or appearance between sexes) called sexual dichromatism (a difference in color between sexes), which is observed in bird species across the world. Below are some photos I took of a few bird species local to Raleigh demonstrating this phenomenon.

The fact that color is sex-specific suggests an origin in sexual selection; this is what Charles Darwin hypothesized over a century ago in Part II, Ch. 8 of The Descent of Man (1871):

There are many other structures and instincts which must have been developed through sexual selection—such as the weapons of offence and the means of defence of the males for fighting with and driving away their rivals—their courage and pugnacity—their various ornaments—their contrivances for producing vocal or instrumental music—and their glands for emitting odours, most of these latter structures serving only to allure or excite the female. It is clear that these characters are the result of sexual and not ordinary selection... When we behold two males fighting for the possession of the female, or several male birds displaying their gorgeous plumage, and performing strange antics before an assembled body of females, we cannot doubt that, though led by instinct, they know what they are about, and consciously exert their mental and bodily powers.

But what is sexual selection? In short, “Sexual selection is that special form of natural selection which is responsible for the evolution of traits that promote success in competition for mates” (Kodric-Brown and Brown, 1984). Birds are excellent subjects for the study of sexual selection since they exhibit so many of its different manifestations, such as with their singing, plumage, and lekking. Sexual selection tends to be most prominent in polygamous species (usually polygynous) in which one sex (usually females) invest more resources in rearing offspring and the other sex (usually males) compete for mates.

How exactly is ornamental plumage a result of sexual selection? There is no straightforward answer, and many theories have been proposed in an attempt to explain this. The mathematical biologist Ronald Fisher hypothesized that the more dramatic cases of sexual selection (such as the exotic plumage of the peacock) were the result of "runaway selection". In summary, a positive trait first arises in males, and females come to associate this trait with higher fitness and prefer it in mates. Exagerration of this trait can elicit stronger preferences in females, creating an evolutionary feedback loop, or runaway selection. Another theory, dubbed the handicap principle and proposed by the biologist Amotz Zahavi, hypothesizes that in sexual selection, costly signals are reliable or "honest". Sexually selected traits behave like handicaps to males and thus communicate a greater overall fitness. To continue with the example of the peacock, large colorful feathers act as a handicap in males because they hinder mobility, flight, and predator evasion. Paradoxically, this showy display communicates to females a greater overall vitality since the male is able to survive despite these handicaps. Another clever application of this principle is in the world of sandwich condiments. Smucker's uses the slogan "With a Name Like Smucker's, It Has To Be Good". The meaning being that with such an unpalatable name as "Smucker", the popularity of their products must be due to their quality, otherwise no one would buy them! These are perhaps the most well known hypotheses, but there are many others I have not mentioned, such as the sexy son hypothesis (1979), the "good genes" hypothesis (1982), etc.

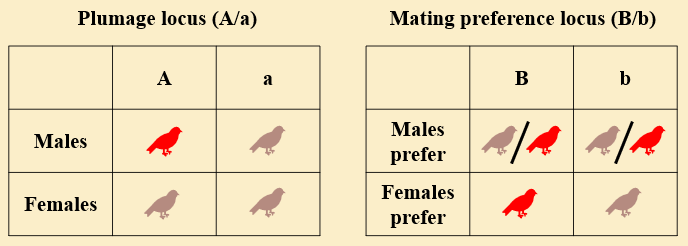

The fundamental idea is that ornamental male plumage indicates certain traits or characteristics desirable to females. In the case of cardinals, evidence suggests that brighter plumage correlates with mate and territory quality [2]. The biological details deserve a post their own, but let's move on to studying sexual selection in birds with a simple mathematical model. For simplicity, let's assume our birds are haploid, and that plumage type and preference are determined by a single, biallelic locus each. Bird plumage is either ornamental ($A$) or cryptic ($a$), and only females exercise a preference in mating (males will mate with conspecifics regardless of plumage). Females have a preference for mates with either ornamental ($B$) or cryptic ($b$) plumage. Figure 3 summarizes these assumptions. We further assume that females are always cryptic, so that they do not incur any fitness costs associated with ornamental plumage.

Let $M_{XY}$ and $F_{XY}$ be the proportion of males and females, respectively, with genotype $XY$, and let $\chi_a,\chi_A \in [0,1]$ control the strength of mating preference, i.e. the proportion of females from each encounter with a non-preferred male that instead choose to mate with a male of the preferred plumage. To illustrate, the probability of progeny with genotype $AB$ (i.e., progeny with ornamental plumage with a preference for ornamental plumage) is

Here, $\alpha_A$ is the strength of female preference for male birds with ornamental plumage, and similarly for $\alpha_a$ and female preference for males with cryptic plumage. Notice that if $\alpha_A = 1$, then it is never the case that females with a preference for ornamental males instead mate with a cryptic male. If we set $\alpha_a = \alpha_A = 1$, cryptic-preferring females only mate with cryptic males, and ornamental-preferring females only mate with ornamental males. An important assumption made above is that mating is random so long as the male possesses the preferred plumage. This is obviously not true, as some bird species mate for life (such as house sparrows), and lobsided pairing distributions result in polygynous species with strong sexual selection (male mating follows an approximate winner-take-all scheme). Nonetheless, this is fine for a weekend model. There are four possible genotypes: $AB$, $Ab$, $aB$, and $ab$. Imposing the restriction that $p_{AB} + p_{Ab} + p_{aB} + p_{ab} = 1$ gets

In either case, the proportion of females that instead mate with a more attractive male is equal to the strength of that attraction (controlled by $\alpha_A$ or $\alpha_a$), multiplied by the ratio of unattractive to attractive males. For the population dynamics of our model, we will assume simple logistic growth in addition to a mortality rate that depends on plumage:

Here, $K = 1$ is the carrying capacity of the system, so $M_j$ and $F_j$ respectively denote the proportion of male and female birds with genotype $j$. Females produce clutches with average size $\lambda,$ $N$ is the total population size, and birds die at rate $\mu$. The fitness cost in males (females) with plumage $i$ is denoted by $\phi_{M,i}$ ($\phi_{F,i}$) and modifies bird mortality, keeping with the intuition that ornamental plumage increases risk of predation. We always take that $\phi_{M,a} = \phi_{F,a} = 0$, or that cryptic plumage does not incur a fitness cost. The average lifespan of a male/female with plumage $i$ is

where $*\in\{M,F\}$. So, for $\phi_{M,i} > 0$, the lifespan of males with plumage $i$ is reduced and the trait is deleterious. On the other hand, if $\phi_{M,i} < 0$, then the lifespan of males with plumage $i$ is increased. We can choose parameter values fitting those of several local passerines: $\lambda = 1/3$ per month corresponds to an average of four eggs per year, a lifespan of $1/\mu = 36$ months, and a slight fitness cost in males due to ornamental plumage, or $\phi_{M,A} = 0.1$.

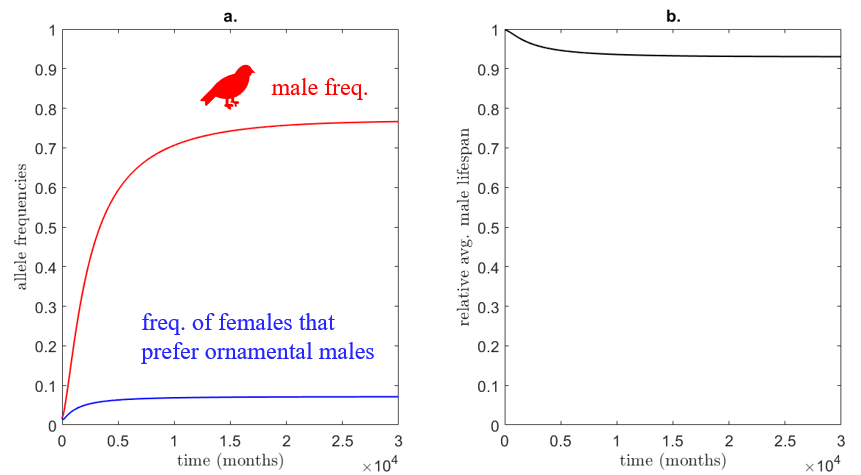

To start with a simple experiment, consider the scenario of a novel mutation arising in a small bird population that produces ornamental plumage in males. Without female preference, the newly introduced allele goes extinct as a result of genetic drift. However, if we also assume a simultaneous mutation arises that produces a female mating preference for male ornamental plumage, the story becomes more interesting. Let $M_{Ab} = F_{aB} = 1/N$ be the initial frequency of males and females with these respective mutations. The remainder of the population has cryptic plumage and mating preference, or $M_{ab} = F_{ab} = (N/2-1)/N$ (the sex ratio is 50:50). Furthermore, let $\alpha_a = 0$ so that cryptic females have no plumage preference in mates (i.e., random mating), and $\alpha_A = 1$ so that females that prefer ornamental males will only mate with ornamental males. The solution of the model in \eqref{birdModel} with these parameters is shown below in Figure 4.

Nearly 80% of males eventually display ornamental plumage, while less than 10% of females have a mate plumage preference! The remainder of females effectively mate randomly since they do not have any plumage preference ($\alpha_a = 0$). This is interesting: males that cater to strong female preferences become the majority in the population, despite these preferences only applying to a small number of females. This all in spite of the fitness cost imposed by the ornamental plumage (although the relative decrease in lifespan is not significant). This raises the question of whether female selectivity and not ornament signal (e.g. vitality) determines male traits. These two possibilities are not exclusive, however, as females can be selective for male traits that signal desirable features in a mate.

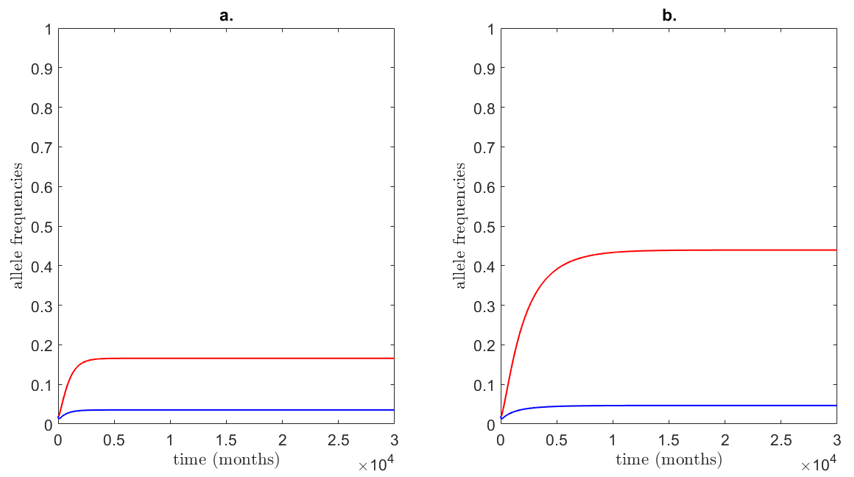

The experiment above assumed that $\alpha_a = 0$, or that females with no mating preference mate randomly. How does the situation change if these females have a slight preference for cryptic mates $(\alpha_a > 0)$? Furthermore, what if the allele producing ornamental mate preference in females is not nearly as selective ($\alpha_A < 1$)? Both of these possibilities are considered in Figure 5.

A weak de novo cryptic-plumage preference dramatically reduces the equilibrium of the ornamental trait in males. This suggests that invasion by a competing sexual ornament is difficult, even if female selectivity for the resident male ornament is weak. As Fig. 5b. shows, reducing the strength of selectivity in females ($\alpha_A$) by only 10% nearly halves the proportion of males with the ornamental trait at equilibrium. Clearly, strong female selectivity is needed for even a slightly deleterious ornament to spread in a population. Then again, over evolutionary timescales, female preference could increase—harkening back to Fisher's theory of runaway selection.

Speaking of this, one thing to notice about the results of all previous experiments is that the ornamental trait is never fixed in the male population. This is unrealistic, as there are no cryptic male cardinals (excluding exceptional cases, such as caused by gynandromorphism). So, how can an ornamental allele become fixed in males using the model in \eqref{birdModel}? The answer lies in the fitness cost. A slightly beneficial ornamental allele in males ($\phi_{M,A} \lessapprox 0$) spreads much more successfully, even if a weak de novo female cryptic-preference exists. Ignoring an existing cryptic-preference, a beneficial allele is much more likely to escape stochastic exctinction if it is buoyed by female preference.

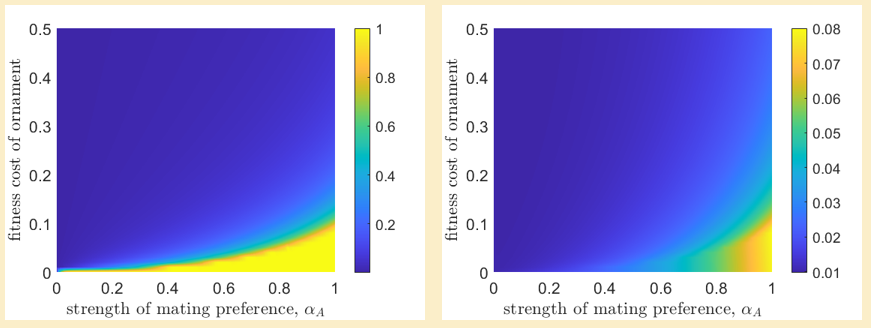

What if we require that the ornamental trait in males be deleterious? Under what conditions can a deleterious trait become fixed in the male population? This question is explored in the plots below.

Deleterious ornamental traits can become fixed in males if the fitness cost is low $(\phi_{M,A} < 0.1)$ and female ornament preference is high ($\alpha_A \gtrapprox 0.5$). Of course, the ornamental traits in some avian species appear much costlier than any cryptic alternatives, such as peacock feathers. In these situations, we would expect $\phi_{M,A} > 0.1$. Then again, our analysis ignores temporal changes to preferences or fitness costs, which might help to explain the ostentatious results observed in the modern day. We have also not considered the possibility of ornaments that impose fitness costs in females as well, such as is the case in club-winged manakins. While these are interesting questions, I can only do what my Saturday afternoons afford me! All code for this project can be found over on my Github.

Finally, since the topic of this post is birds, I couldn't resist but take the opportunity to share a few of my favorite bird pictures, taken during my travels in North Carolina and Maine.

References

[1] Kodric-Brown, A., and J. H. Brown (1984). Truth in Advertising: The Kinds of Traits Favored by Sexual Selection. The American Naturalist. 124(3); 309-23.

[2] Wolfenbarger, L. L. (1999). Red coloration of male northern cardinals correlates with mate quality and territory quality. Behavioral Ecology. 10(1); 80–90.